“It shows how literature… can trace another path for memory, next to the historical account.”

The irony is that few in Algeria are likely to read it. The book has no Algerian publisher; the French publisher Gallimard has been excluded from the Algiers Book Fair, and news of Daoud’s Goncourt success has – a day on – still not been reported in the Algerian media.

Worse, Daoud – who now lives in Paris – could even face criminal charges for speaking of the civil war.

A 2005 “reconciliation” law makes it a crime punishable by jail to “instrumentalise the wounds of the national tragedy”.

According to Daoud, the effect is to make the civil war – which traumatised the entire country – a non-subject.

“My 14 year-old daughter did not believe me when I told her about what had happened, because the war is not taught in schools,” Daoud told Le Monde newspaper.

“I cut out some of the worst scenes I wrote. Not because they were untrue, but because people would not believe me.”

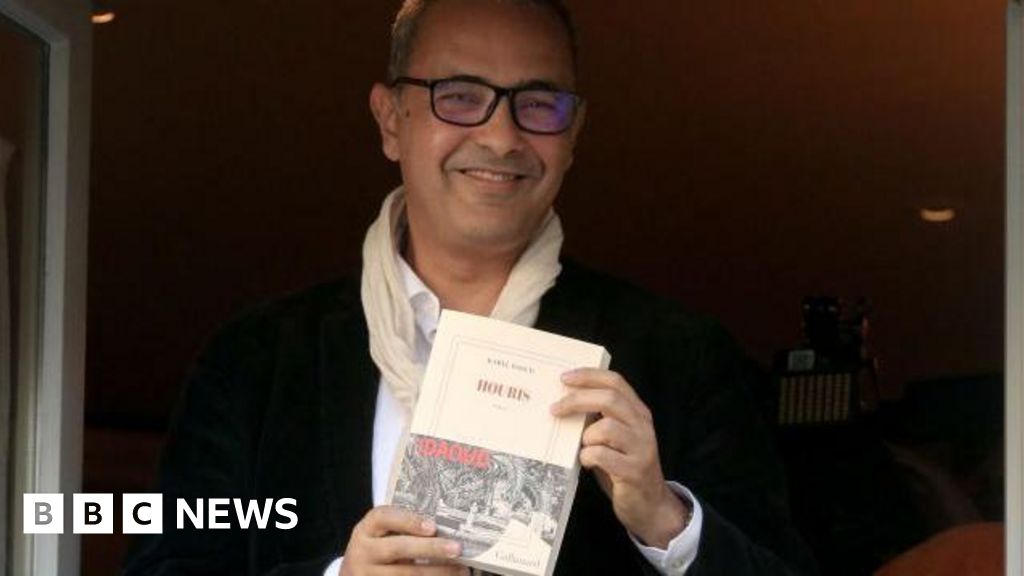

Daoud, 54, had first-hand experience of the massacres because he was a journalist at the time working for the Quotidien d’Oran newspaper. In interviews he has described the ghastly routine of counting corpses, then seeing his count altered – up or down – by the authorities, depending on the message they wanted to be given.

“You develop a routine,” he said. “Come back, write your piece, then get drunk.”