Youth unemployment is shaping up as a major obstacle in India’s efforts to maintain one of the world’s fastest growing economies. NHK World spoke with former central bank governor Raghuram Rajan on potential solutions.

India’s GDP grew by 8.2 percent in 2023-2024, up 1.2 percentage points from the previous year. Manufacturing, construction, real estate, and financial services led the way. With a population of 1.4 billion, the IMF predicts the South Asian nation will be the 3rd largest economy by 2027, overtaking Germany and Japan.

Despite that promising outlook, many economists say India’s main challenge for economic growth is finding productive employment for its large pool of young people.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s solution focuses on attracting foreign investment into the manufacturing sector, under the slogan “Make in India.”

Semiconductor factories are a good example. Just this March, a launch ceremony was held for three chip factories that came with investments totaling around 15 billion dollars.

This follows a similar path taken by countries like Japan and China that grew by focusing on manufacturing. Factories employ low-skilled workers, many of whom have been engaged in agriculture. These workers eventually acquire skills to be more productive, earning higher wages, leading to a bigger middle class.

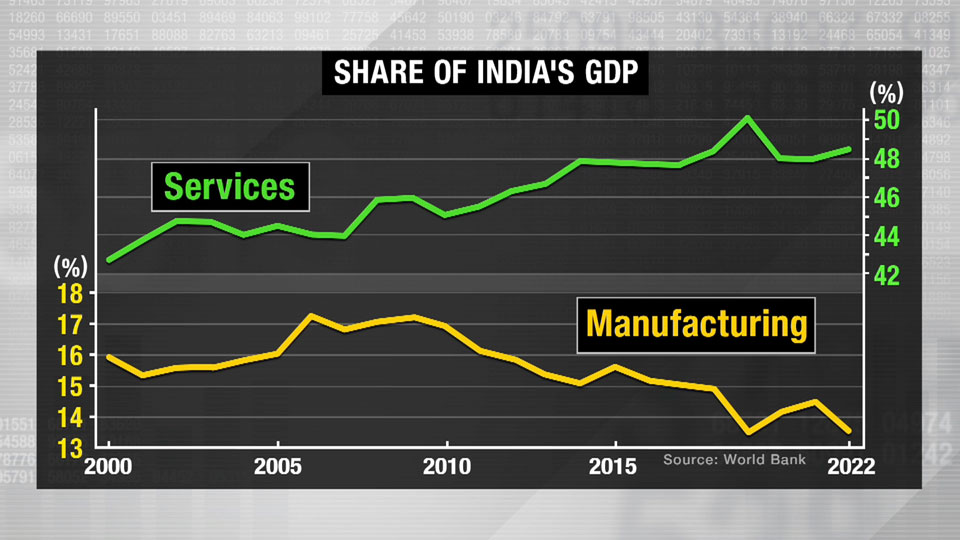

Unfortunately, that strategy doesn’t seem to be bearing fruit in India. Manufacturing growth has been stagnant for the past two decades, with the sector making up just over 10 percent of GDP. What is growing instead are services such as IT and retail, which account for close to 50 percent of GDP.

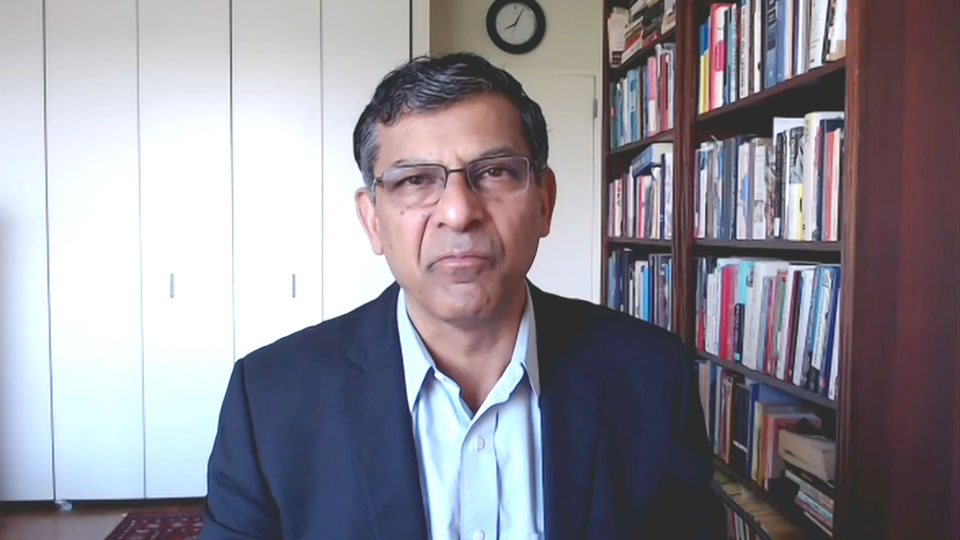

Raghuram Rajan, a former governor of India’s central bank and now a professor at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, argues that manufacturing is not the solution for youth employment.

Rajan notes that when Japan and China expanded their manufacturing sectors, the environment was different: they were competing with industrialized countries in Europe and the United States, benefiting from cheap labor to offset the lack of good management, capital, and efficient infrastructure.

“India is not competing with the West or Japan, it is competing with China, which still has many poor workers in the western provinces. It is competing with Vietnam. It is competing with Bangladesh.”

Global outsourcing of factories means India doesn’t have the advantage in manufacturing that developing countries had in the past.

Rajan says India’s leading sector should be services – with the emphasis on high skilled service exports.

“Some of the biggest employers in India in terms of value added are foreign firms who are looking to build offices full of engineers, lawyers, consultants, etc., all of whom are working for the parent company for projects across the world.”

Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan already have a strong presence in India. Rajan says, given the improvements in communication technology, India’s services exports could expand greatly if the government spends more on education: “The government could fund six months training to thousands of students that graduate from universities to give them the latest IT training to meet the demands of foreign firms.”

The former central bank chief stresses that he is not against manufacturing per se. His beef is that India is not playing to its strengths.

“The enormous government spending on subsidies for capital-intensive chip manufacturing to my mind seems misplaced, because you’re trying to get people to come despite the impediments, like the lack of skilled labor and infrastructure.

“On the other hand, foreign firms come looking for workers in services, who are happy to come in without any subsidies, and are employing a lot of people.”

Rajan says India should enter manufacturing where it has a competitive advantage, mainly in the upper part of the supply chain for engineering and design.

“What India needs to do is make many more of these workers of the quality sought by these large firms so it can expand this sector to create its own chip designers, its own Nvidia, its own Qualcomm.”

Ranjan warns that India’s demographic advantage will decline in the middle of the century. He says the window of opportunity is narrowing, and the authorities need to give more thought to the economic policies they pursue.

“India could take a path that no other country has taken.”