There is an ‘unhealthy magic circle’ of senior leaders who are allowed to move from one hospital to another in the NHS despite past failings, the public inquiry investigating Lucy Letby‘s crimes heard today.

Sir Rob Behrens, the former parliamentary and health service ombudsman, agreed the ‘revolving door’ made it ‘difficult’ for new people to get top jobs in the health service.

He called for the Government to bring in a new regulatory body with the power to ban senior executives, often on six-figure salaries, from taking up senior posts if they are found guilty of serious misconduct.

But he also suggested a ‘competency framework’ was needed to annually assess their performance and help them learn from mistakes.

‘One difficulty I’ve witnessed is there’s an element of the magic circle about leaders in the NHS,’ Sir Rob said.

‘People tend to go from one (Trust) to another, it’s more difficult for new people to come in.

‘That magic circle is not healthy, but where there is no competency framework, and where you can’t take notice of the failure of people in their previous jobs, then it becomes self-limiting and too narrow.’

There is an ‘unhealthy magic circle’ of senior leaders who are allowed to move from one hospital to another in the NHS despite past failings, the public inquiry investigating Lucy Letby’s crimes heard today. Pictured: Lucy Letby

The Thirlwall Inquiry, sitting in Liverpool, has heard NHS Improvement tried to help Tony Chambers, the former chief executive of the Countess of Chester Hospital, find a new role if he agreed to step aside when paediatricians indicated they wanted to hold a secret vote of no confidence in his leadership.

The medics have given evidence that they felt ‘bullied’ and ‘victimised’ by Mr Chambers, and other senior leaders at the Trust, who threatened them with disciplinary action and referral to the General Medical Council when they tried to blow the whistle about Letby.

Mr Chambers, who earned £160,000-a-year at the Countess, went on to hold senior posts at other NHS hospitals after he resigned, in September 2018, soon after the former neo-natal nurse was first arrested by police.

He and then medical director, Ian Harvey, have also been accused of putting the hospital’s reputation before the safety of the premature babies who were murdered and harmed by Letby, between June2015 and June 2016.

Sir Rob, who was the parliamentary and health service ombudsman between April 2017 and March this year, added: ‘Time and time again we’ve seen senior managers and boards are more interested in protecting the reputation of their organisation rather than dealing with patient safety issues.

‘This must have something to do with the culture of the leaders of the health service and it must have something to do with the absence of a competency framework in which these people operate.

That goes really to the heart of what’s wrong with the leadership of the NHS.

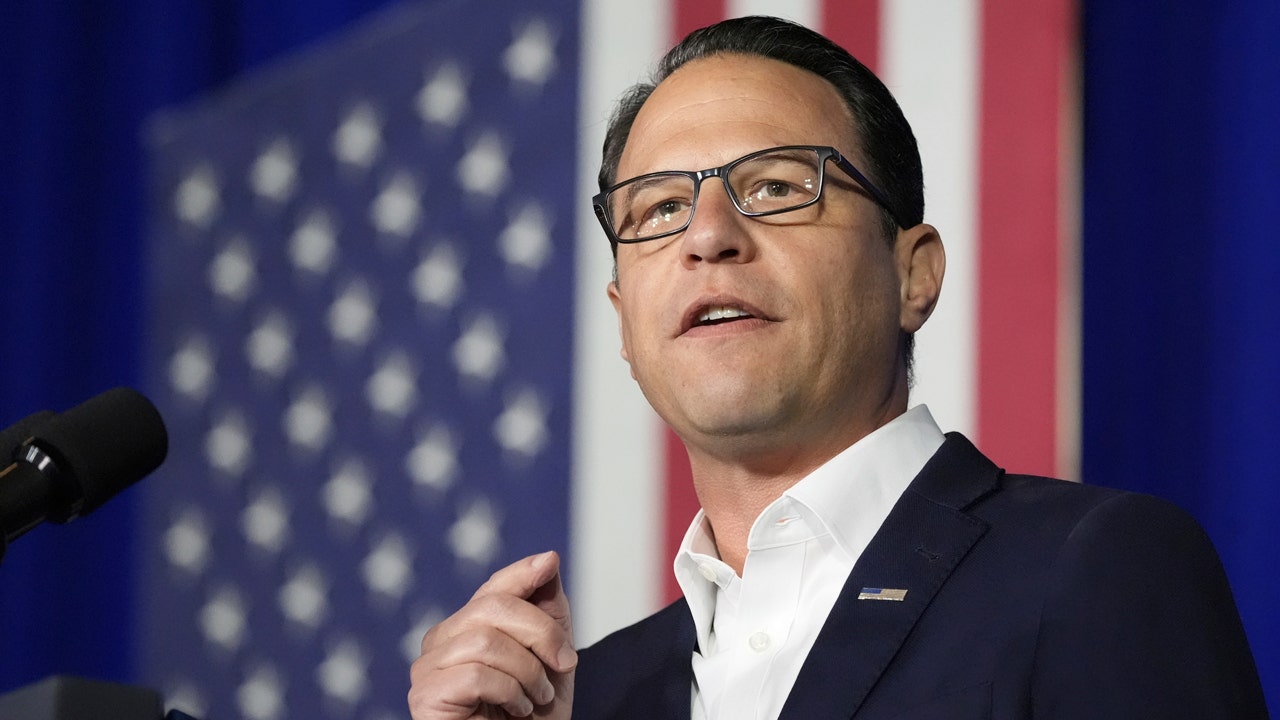

Sir Rob Behrens, the former parliamentary and health service ombudsman (pictured), agreed the ‘revolving door’ made it ‘difficult’ for new people to get top jobs in the health service

Historically, there has been insufficient emphasis on patent safety to make leaders convinced that they have to put that first.’

Sir Rob also said laws designed to protect NHS whistleblowers in England ‘do not work’ and too many doctors had contacted him during his tenure to say they were fearful of raising patient safety concerns in case it ruined their careers.

‘Puny fines’ also had no impact on leaders who failed to adhere to the NHS’s duty of candour, he said.

Sir Rob insisted ‘political leadership’ is needed to enact cultural change in the NHS, but he also pointed out that, historically, the Government had failed to implement reforms following successive NHS scandals.

He said there is currently no professional body or ‘watchdog’ overseeing the implementation of recommendations from public inquiries and people had become ‘too used to seeing repeated failings.’

Sir Rob gave the example of the ‘chastening’ reviews, by Dr Bill Kirkup, who examined failings in maternity services at hospitals in Morecambe Bay and East Kent, seven years apart, as evidence of a ‘worrying acceptance’ and ‘inertia’ in improving patient safety in the NHS.

‘He (Dr Kirkup) wrote at the end of his inquiry into East Kent that there’s no point in me making detailed recommendations because what I’ve proposed before has not been adopted,’ Sir Rob said.

‘The same issues are relevant as they were 10 years ago. The failure of teamwork among clinicians, the failure to listen to patients and families, the failure to investigate appropriately and the failure of the board to be interested in what’s going on. That’s very worrying.’

He suggested the National Audit Office or some other ‘prestigious public body’ should be given the responsibility for making sure recommendations of public inquiries are enforced.

Letby, 34, from Hereford, is serving 15 whole-life orders after she was convicted at Manchester Crown Court of murdering seven infants and attempting to murder seven others, with two attempts on one of her victims, between June 2015 and June 2016.

The inquiry, sitting at Liverpool Town Hall, will hear evidence until January, with findings expected to be published in autumn 2025.