Illustration: Barbara Gibson. Images: Getty/Alamy

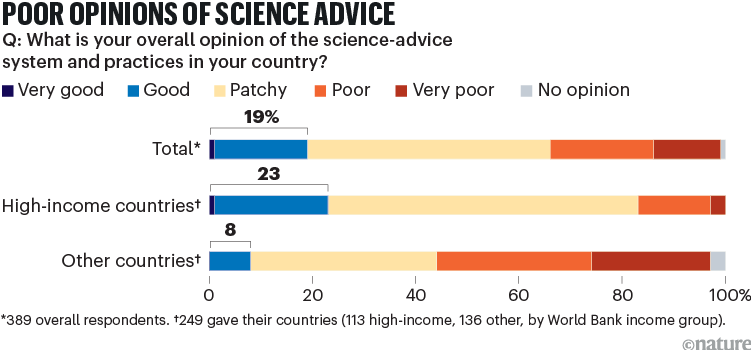

Killer viruses. Artificial intelligence. Extreme weather. Microplastics. Mental health. These are just a few of the pressing issues on which governments need science to inform their policies. But the systems that connect scientists with politicians are not working well, according to a Nature survey of around 400 science-policy specialists around the world. Eighty per cent said their country’s science-advice system was either poor or patchy, and 70% said that governments are not routinely using such advice.

“Every country is asking how we can do science and scientific advice,” says Jeremy Farrar, chief scientist at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland. Five years after the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the importance of strong links between scientists and policymakers, the challenges to providing advice have grown. Spiralling mis- and disinformation risks obscuring science advice, while anti-science sentiment is eroding trust in experts and evidence — a phenomenon that scientists worry will worsen under the second US presidency of Donald Trump, who has repeatedly ignored or distorted evidence from research.

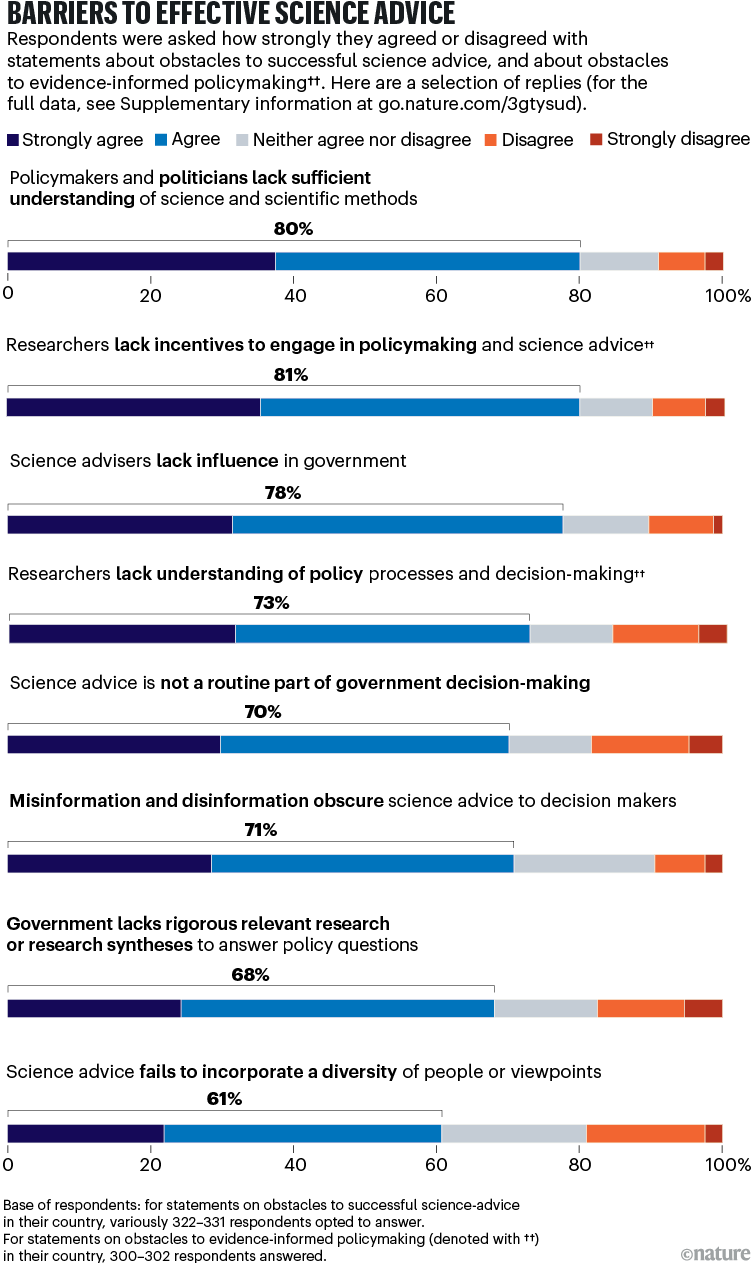

Nature’s survey — which took place before the US election in November — together with more than 20 interviews, revealed where some of the biggest obstacles to providing science advice lie. Eighty per cent of respondents thought policymakers lack sufficient understanding of science — but 73% said that researchers don’t understand how policy works. “It’s a constant tension between the scientifically illiterate and the politically clueless,” says Paul Dufour, a policy specialist at the University of Ottawa in Canada.

But it’s a time of reinvention and evolution in science advice, too. Finland is one country experimenting with different models for providing advice. Many groups, including the US National Academy of Sciences in Washington DC, are trying to speed up the supply of advice to match the rapid pace at which policymakers work, or to incorporate conflicting views. Last year, the United Nations secretary-general, António Guterres, launched a Scientific Advisory Board.

Many people in the field say that science-advice systems need further change. Tackling issues such as intergenerational disadvantage, youth mental health, immigration and responses to climate change require different ways of operating, says Peter Gluckman, former chief science adviser to the New Zealand prime minister and now at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. “Science advice is not designed for that at the moment.”

Whenever there was a scientific crisis at London’s 10 Downing Street in the mid-1960s, someone would bellow down the hall for Solly Zuckerman, the United Kingdom’s first government chief scientific adviser (GCSA). Zuckerman, a physician, had guided the government on military planning during the Second World War and was appointed as GCSA by prime minister Harold Wilson in 1964.

Legend has it that Zuckerman would arrive, say his piece and smoothly exit — and that, mysteriously, once the controversy was over, there would be no sign he’d been involved. Aside from the lack of transparency, “that kind of summarizes how science advice should work”, says Mark Ferguson, who was chief science adviser to the government of Ireland from 2012 to 2022 and has since retired.

Why we need a body to oversee how science is used by governments

Zuckerman’s legacy is the chief science advisers (CSAs) that many Commonwealth and other countries have today. In the United Kingdom, the GCSA heads the Government Office for Science, which advises the prime minister and Cabinet Office, while government departments have their own CSAs alongside various councils, committees and more. The system is sometimes referred to as “the Rolls Royce of science advice”, says Kathryn Oliver, who studies the use of evidence in policy at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. It is also so complex that it took one report 93 pages to explain (see go.nature.com/4fj5tq4).

In other countries, national academies of scholars have a more central role. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in Washington DC are a key pillar of US science advice, along with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and its director, who advises the president. There are also myriad other ways that research informs branches of the US government.

Advising governments about science is essential but difficult. So train people to do it

“There’s no ‘one size fits all’,” in science advice, says Chagun Basha, chief policy adviser in the Office of the Principal Scientific Adviser to the Government of India, who is based in Bengalaru. Each country has evolved its own system, shaped by history, culture and crises it has faced. Japan has the Council for Science, Technology and Innovation, among other means of providing advice. China has the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Chile has ad hoc committees. And at least half of countries do not have science-advice systems with a chief adviser and staff, although they might have other ways to bring evidence into policy, says Soledad Quiroz, who studies knowledge management at the Central University of Chile in Santiago.

But science-advice systems do have one thing in common: many people think they’re not up to the job: 78% of respondents to Nature’s survey said that science advisers lack influence in government and 68% felt that governments lack the relevant research to answer policy questions. “I don’t think any country has got it right, and I don’t know what right would look like,” says Oliver.

What’s more, Oliver says, the definition of science advice is unclear. To some, it is confined to the formal mechanisms — such as academies and science advisers — by which a government accesses scientific evidence to inform policies and decisions. Others use it loosely to refer to any way in which research informs policy, including think tanks and bureaucrats googling for facts. “Taxi drivers are good at giving science advice,” says Rémi Quirion, chief scientist of Quebec in Canada, drily.

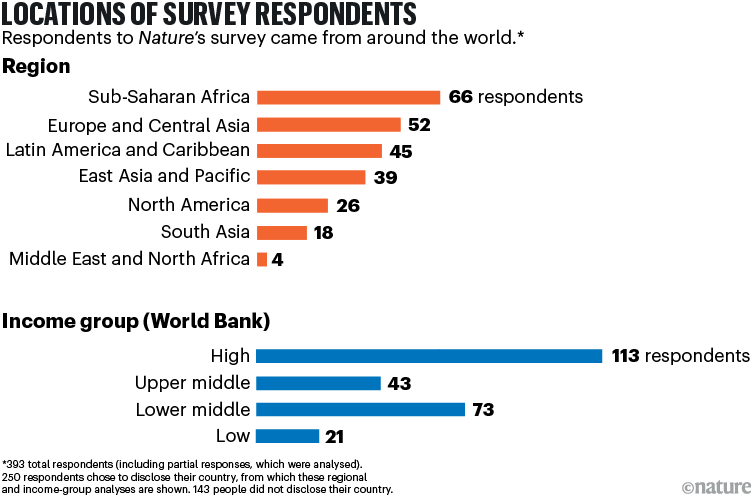

Nature’s survey on science advice was sent to about 6,000 people around the globe, most of them on the e-mail list of the International Network for Governmental Science Advice (INGSA), which is based in New Zealand. Roughly half of respondents worked in research, and half in government or an advisory group. (Respondents could work both in research and in government or advisory roles.) They were asked about the quality of routine science advice to governments and about advice during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic (see ‘Locations of survey respondents’; for full data, see supplementary information).

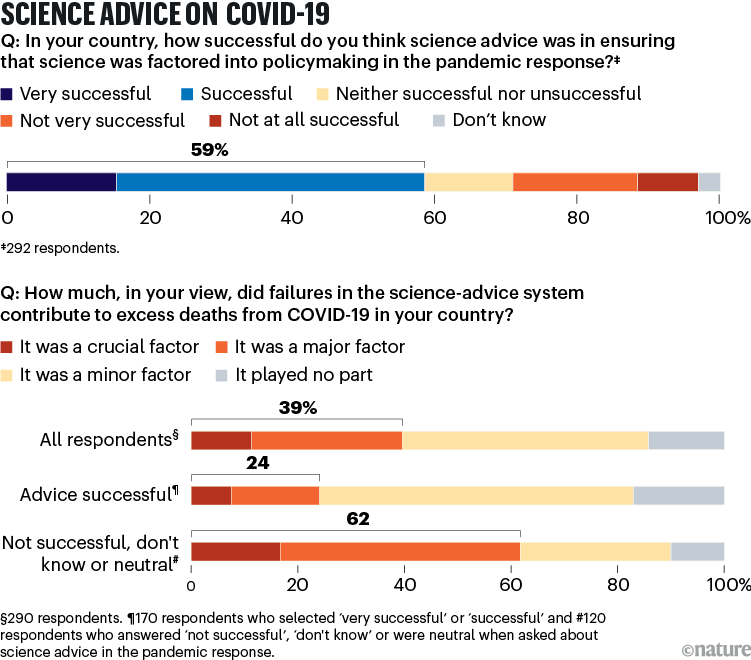

In interviews, experts said that the pandemic was a key turning point in global science advice because it stress-tested systems and revealed their strengths and weaknesses. In the survey, views on the outcome were mixed. Nearly 60% of participants said that science advice was successfully factored into pandemic policymaking in their country (see ‘Response to COVID-19’). But one-quarter of this group also said that failures in science advice were a major contributor to COVID-19 excess deaths, which amounted to more than 21 million in 2021–22, according to one estimate (see go.nature.com/3gxfvo9).

In September 2020, as the death toll rose, science-policy researcher Roger Pielke at the University of Colorado, Boulder, started a project called Evaluation of Science Advice in a Pandemic Emergency. More than 100 researchers helped to produce case studies of government science-advisory mechanisms in places from Sweden to Hong Kong.

The number-one lesson, Pielke says, was that “no one really got it right”. Number two was that the United States looked particularly bad. That science was not informing top US politicians was glaringly obvious when then-president Donald Trump made press-conference statements that science did not support — for example, stating that the anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine could treat COVID-19. Immunologist Anthony Fauci, a US science adviser and member of the White House coronavirus task force, raced to correct him.

Scientists are building giant ‘evidence banks’ to create policies that actually work

To Pielke, COVID-19 exposed the United States’ lack of a high-level expert advisory mechanism to inform the government’s response — one equivalent to the United Kingdom’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), for instance. “Given that the United States is kind of the world’s colossus of scientific research, it’s a shocking oversight,” he says.

“No one knew who was in charge” of science advice in public health, says Marcia McNutt, president of the US National Academy of Sciences. The academy was releasing advice, but various health and science agencies were interpreting it disparately, she says. The biggest win post-pandemic, she says, would be to work out who should take the lead next time.

Globally, the fast-moving pandemic highlighted that many science advice systems are simply too slow in a crisis. The US National Research Council, which conducts studies for the National Academies, had seen a gradual drop in requests for its signature reports because policymakers couldn’t wait the 18 months they typically took to produce. During the pandemic, the council fast-tracked some reports in just a few weeks. The academy announced plans in its 2024 strategy to build a standing capacity to work at this pace.