The first quarterly expansion in a year. Recession receding into the rear-view mirror. A stronger performance in recent months than the Bank of England and the City had thought likely. Faster growth in early 2024 than any other member of the G7 group of leading industrial nations.

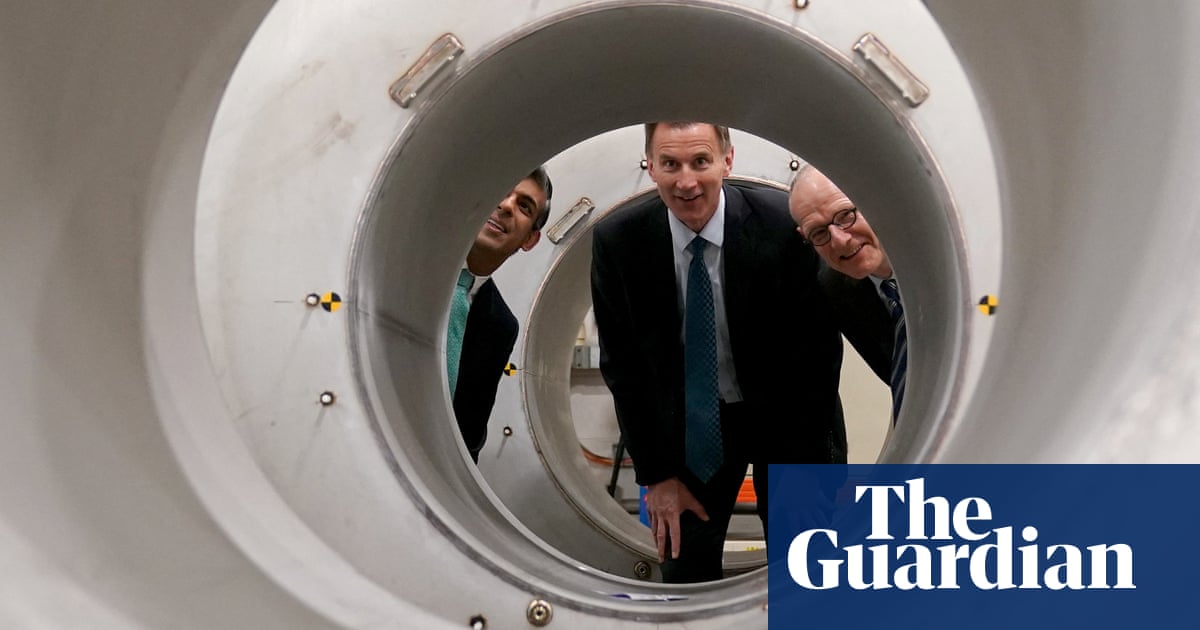

When you are in as deep a political hole as the current government you seize on any good news, and there was plenty for Jeremy Hunt to choose from in the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics. The figures were proof that the economy was returning to “full health for the first time since the pandemic”, the chancellor said.

Yet when people look back on the early months of 2024 they will probably remember the relentlessly awful weather rather than a time when the economy was cooking with gas. Boom-boom Britain it certainly isn’t.

To be sure, the UK has emerged from recession but the downturn in the second half of 2023 was a much more modest affair than some of the monster downturns of the past 50 years. The hollowing out of manufacturing in the early 1980s was a genuine slump, as was the housing market crash in the early 1990s and the near collapse of the banks in the global financial crisis of 2008.

The bigger picture is that Britain’s growth performance during the current parliament has been extremely weak. National output as measured by gross domestic product is only 1.7% above pre-pandemic levels, and adjusted for a rising population per capita, growth has actually fallen – by 1.2%. As things stand, this is on course to be the first parliament in living memory to have seen falling living standards over the term.

There are reasons for that. Mistakes have clearly been made, most starkly during Liz Truss’s seven-week premiership, but the economic narrative of the past five years has been shaped by two huge external shocks. The response to the global pandemic that arrived in the UK in early 2020 meant the economy contracted by almost 25% in March and April of that year. The economy was almost 10% smaller in 2020 than it was in 2019.

The UK bounced back relatively quickly from the lockdown-induced slump but was then hit by a second setback: the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Rising energy costs meant inflation, already rising as global demand soared in the post-lockdown period, was given another upward twist. Central banks raised interest rates aggressively in response.

Smoothing out the ups and downs of the quarterly GDP figures, the economy went sideways in 2022 and 2023. The two successive quarters of negative growth in the second half of 2023 met the technical definition of recession but the downturn might eventually be revised away when fresh data comes in. Most forecasters were expecting something worse, with the Bank of England predicting the longest recession in 100 years.

Rob Wood, a UK economist at the consultancy Pantheon Macroeconomics, said the economy had rebounded strongly in the first quarter but that its performance overall since the arrival of Covid-19 four years ago had been disappointing. Given everything it had suffered – not only the pandemic but an energy crisis, soaring inflation and much higher levels of interest rates – that was not entirely surprising, Wood added. Indeed, it was “remarkable” the UK had grown at all.

There has also been a significant divergence between sectors and between regions. Services, which make up about 80% of national output, have done a lot better than manufacturing or construction, and within services, business and finance firms have performed more strongly than those serving consumers.

Consumer-facing services have been at the sharp end of the cost of living crisis, with people cutting back on their discretionary spending to save money. But even there, Wood says, there have been winners and losers: pubs have done poorly but art galleries and sporting events have done well.

The patchy performance of the service sector is something that has also been picked up by the Bank of England’s regional agents, who act as the eyes and ears of interest-rate setters on Threadneedle Street’s monetary policy committee.

after newsletter promotion

“Contacts have been surprised by the weakness in consumer spending on goods and services in the first quarter of 2024 and are revising down their expectations of growth for 2024,” according to the intelligence collated by the agents in the six weeks to mid-April.

While some of the weakness in spending was because of bad weather, there was also a sense that underlying demand had weakened, although the agents’ contacts were unsure as to the reason. Pubs, restaurants and fast food outlets were suffering because people were increasingly eating at home, but airports were busy, with holiday traffic above pre-pandemic levels.

The strong performance of financial and business services has meant the gap between London and the south-east and the rest of the country has widened. Prof Adrian Pabst, a deputy director for public policy at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research thinktank, says the West Midlands has done particularly poorly, a function he says of a lack of investment and the region’s manufacturers being hard hit by Brexit red tape.

“Despite some efforts, regional inequalities are persistent and, in some cases, getting worse,” Pabst said. “Besides more targeted policies on skills, housing and transport, the country also needs more at-scale investment to regenerate the regions and close the gap with top-performing areas.”

Survey evidence has suggested the economy’s strong start to 2024 has continued into the second quarter. But as Rachel Reeves pointed out last week, there is currently a gap between what the ONS says and what the public thinks. “We won’t have turned a corner until working people feel they are better off,” the shadow chancellor said. At present, there is little evidence that they do.